Researchers from the EvoAdapta Group at UC contribute to uncovering the links between humans and whales in the Bay of Biscay at the end of the Paleolithic

Between 20,000 and 14,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers living around the Bay of Biscay took advantage of the carcasses of at least five whale species, not only to extract fat and baleen but also to craft tools from their bones. An international team of specialists—combining archaeology, proteomics, stable isotope analysis, and radiocarbon dating—offers an unprecedented view of the interactions between humans and large cetaceans at the end of the last Ice Age, a relationship that until now had remained unknown.

Alexandre Lefebvre, Ana B. Marín-Arroyo, and Leire Torres-Iglesias, members of the EvoAdapta research group, are part of the multidisciplinary and international team that carried out this research, published in Nature Communications.

At the end of the last glaciation, around 20,000 years ago, sea levels reached their historical minimum and, during the subsequent thaw, the ocean rose by more than 100 meters, submerging the coasts that Paleolithic groups had once known. This massive geographic transformation has limited our understanding of coastal ecology and marine practices of Europe’s earliest inhabitants.

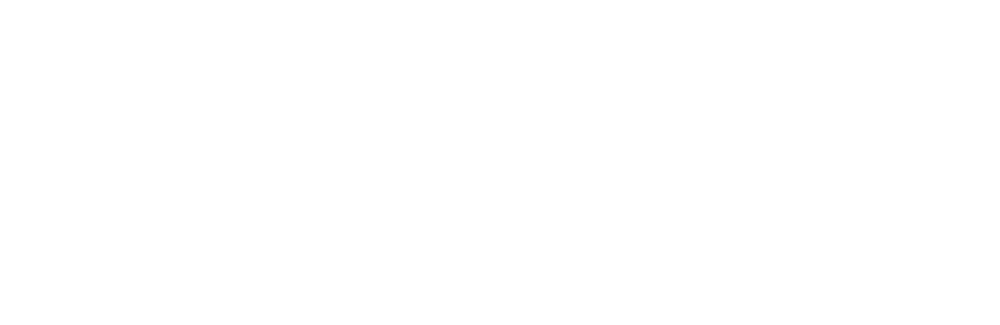

Traditionally, Magdalenian groups of southwestern Europe have been portrayed as large-scale hunters of terrestrial herbivores. However, over the past two decades, discoveries in the interior of the Iberian Peninsula—including remains of fish, seabirds, and mollusks—have pointed to the regular exploitation of marine resources. The new study, published in Nature Communications, expands this perspective by revealing 70 whale-bone tools from sites in southwestern France and northern Spain, as well as 60 additional tools found in a cave in the Basque Country.

Through proteomic identification of collagen, isotopic measurements, and radiocarbon analyses, the team identified remains of blue whale, gray whale, fin whale, sperm whale, and right or bowhead whale. These species, which had diets similar to those observed today, suggest a cetacean biodiversity in the Bay of Biscay comparable to that of present-day Arctic ecosystems—an inference further supported by reconstructed sea temperatures of that time.

The results confirm that the specimens exploited came from natural strandings on beaches between 20,000 and 14,000 years ago. In addition to using the bones to make tools—mainly for carving and engraving activities—Paleolithic groups also extracted fat and baleen, incorporating these resources into their material culture and subsistence economy.

This project, led by the CNRS and the French National Museum of Natural History, involved collaboration with the universities of Cantabria, Barcelona, British Columbia, Montpellier, Toulouse, and Vienna. It was supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR-18-CE27-0018) and by European Union programs (PCI2021-122053-2B; HORIZON-MSCA-2021-PF-01-101059605) based at the University of Cantabria under the direction of Alexandre Lefebvre.